For a long time, Frances Nadeau was something of a mystery to the GMM Team. Thanks to her admission records, we knew that she was Irish-born from Co. Armagh, a Catholic, and a mother with a history of post-partum psychosis. She was a patient during Dr. Joseph Workman’s time in charge of the PLA, but we had no idea about her maiden name until quite recently, thanks to an Ancestry.com search. Without something as simple and yet important as her last name, we often felt we had no real sense of her.

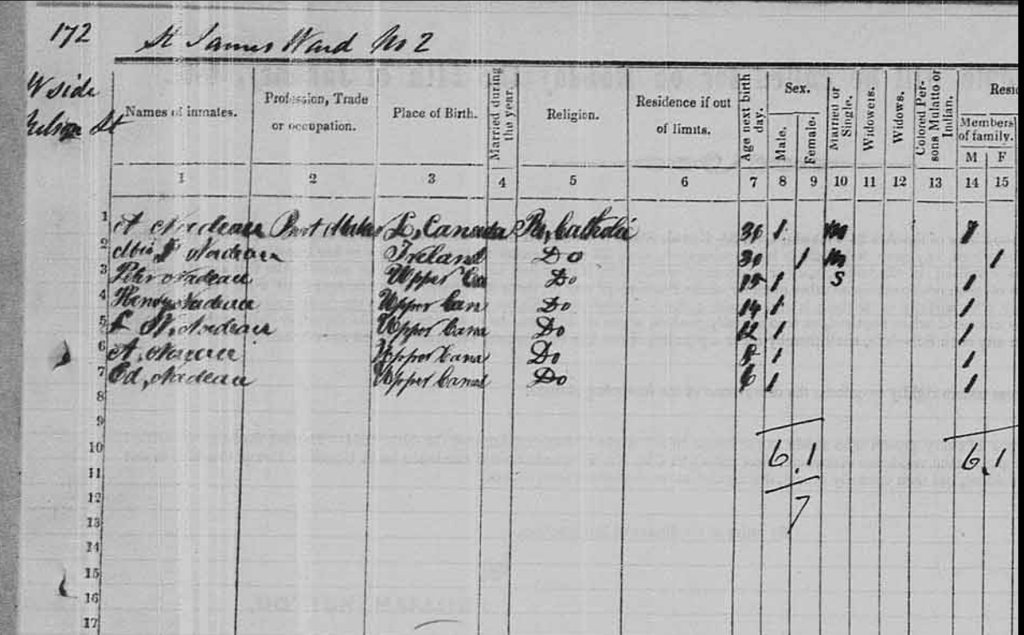

She had married Alexander Nadeau, a shoemaker from Lower Canada—he’s a shoemaker in the asylum records, but a ‘bootmaker’ according to the 1861 census—and that they settled in Niagara for a time. Eventually, they relocated to Nelson Street, only 2.5 kilometres away from the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, straight down Queen Street West. Perhaps they arrived in Toronto for Alexander’s work; or, perhaps, they came because it was closer to the asylum, the place of Frances’ many confinements.

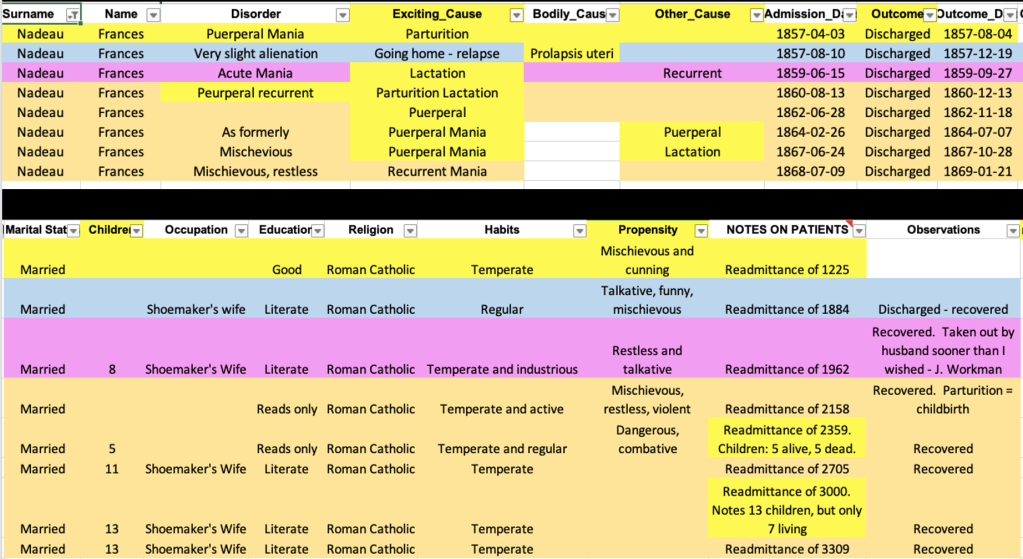

Between 1857 and 1868, Frances was admitted eight times to the asylum. Seven of these events were directly related to her pregnancies: she was confined due to puerperal mania, lactation, and a prolapsed uterus. From her first stay onwards, her admission records noted that she was ‘mischievous’ and talkative. By her fourth return to the asylum, she was considered violent and dangerous. In each instance, she was discharged after a stay of three to five months.

Interestingly, in 1859, Dr. Workman noted on her file that she had recovered, but that Frances had been “taken out by her husband sooner than I wished.” Why did Alexander do this? Was she needed at home? Was he worried about the kind of treatment she was receiving at the asylum, which had more or less become a convalescent home for her after each birth? Had it just become habit for her to rest and be treated at the asylum, and then return to their life together? Our only indication that, perhaps, she was not yet ready to go home was Workman’s tiny jotting on the admission register.

By cross-referencing with other available documents, we can get a better picture of why Frances might have gone insane. On the 1861 census, Frances and Alexander were listed as having five living sons, ranging in age from 15 to 6. But her asylum admissions papers a year later stated that she had five children living and five dead—something the census does not always record, unless the death happened within a year of the census-taker’s arrival at their door. By 1867, Frances had given birth thirteen times, with seven living children and six dead.

For the Nadeau family, the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto provided much needed maternal health care and medical support in the initial months after each of Frances’ later pregnancies. What isn’t listed, however, is to what extent the deaths of six of her children affected the recurrence of her postpartum mania with each subsequent pregnancy. Grief can appear in the medical records as part of a diagnosis, but it was not a standard procedure to note down patients’ emotions. We only get glimpses of the inner turmoil a mother like Frances must have suffered.

Frances’ case as a post-partum patient was very common. At least 31% of the Irish-born female admissions to the PLA between 1841 and 1868 were directly related to pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum complications. If we broaden the criteria to include anything related to a woman’s reproductive cycle or physical complications from menstruation, menopause, pregnancy, or childbirth, that number rises to 43%.

‘Female troubles’ were very much a recurring issue at the PLA in the years leading up to Canadian Confederation.