Dennis McNamara was at the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto in the mid-to-late 1840s. His records demonstrate the great disparity that can exist across a single person’s medical file – even the spelling of his first name wasn’t consistent – while also showing how repeat admissions to the asylum became more notable only a few years after the PLA had first opened its doors.

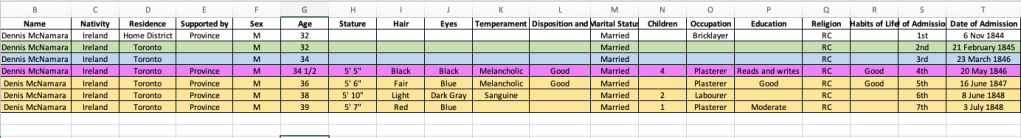

Dennis was first admitted to the asylum on 6 November 1844 when he was 32 years old. He was Catholic, married, the father of several children (the numbers vary, but it seems he had at least four), and had been working as a bricklayer before his committal. He was also later listed as a plasterer and general “labourer.” He could read and write, and was usually judged to have “good” hygiene and general habits.

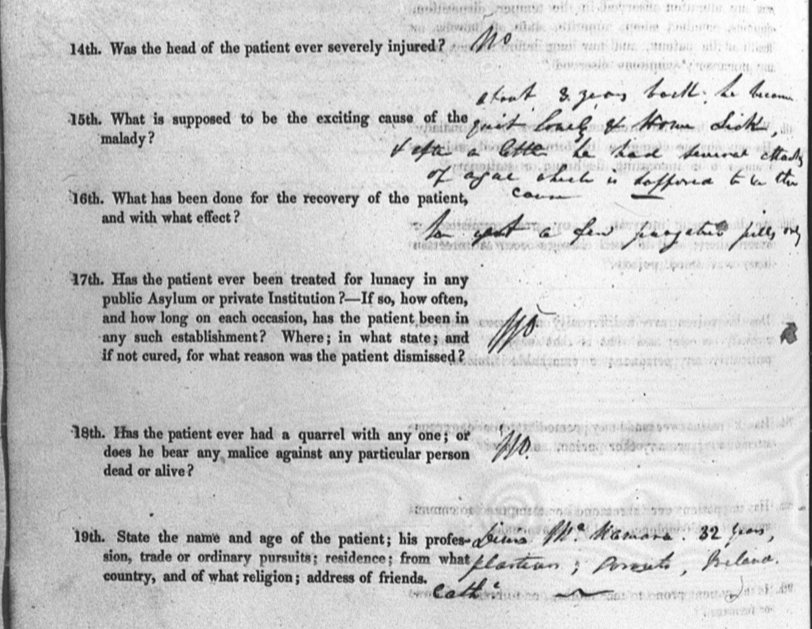

One of the most intriguing records we have about Dennis is the questionnaire that accompanied his first admission. This gives us greater insight into how his family (his wife?) presented him to the medical authorities at the asylum. Apparently, Dennis had been “insane” for the previous four months. This was also not his first bout with mental illness; he had previously had an “attack” some three years before. In the summer of 1844, Dennis had become increasingly “restless at night & generally costive and irregular in his evacuations.” When raving, he allegedly focused “principally on religious matters” and was “under the impression that he is called upon to convert his fellow men.”

Unlike many of his fellow Irish patients, however, Dennis was not described as either violent or destructive. He had no prior infirmities, diseases, or head injuries. The stated “exciting cause” for his 1844 admission was that, “About three years back, he became quite lonely and home sick [sic], and after a little he had several attacks of ague which is supposed to be the cause.” The only medicine that he had taken was a series of “purgative pills.”

Dennis was discharged after only ten days, returning home on 16 November 1844. However, this was just the start of a series of readmissions to the asylum. In total, Dennis was sent to the PLA seven times between 1844 and 1848; his shortest stay was six days, while his longest was nearly one-and-a-half months.

When his records are put together, we can begin to visualise how he appeared during his weeks in the asylum: quiet, despondent, worrying about his family, feeling homesick for Ireland, and suffering from indigestion.

But then there are the discrepancies between his entries. In 1846, Dennis was described as having both black hair and eyes, while standing 5’5”. In 1847, he had grown an inch and then even more to a height of 5’10” in June 1848. One month later, however, he had shrunk to 5’7”. Obviously, this points more to a lack of record-checking on the part of the person recording details in the admissions register than anything mysterious about Dennis himself.

Along a similar but perhaps even more perplexing line is that Dennis’ hair changed from black to fair to light to red, while his eyes changed from black to dark grey to blue. We do know this is the same patient, however, because the ledger clearly indicates that this was the readmission of a previous patient with the correct identification number.

Most distressing of all, perhaps, is the column marked ‘children.’ In 1846, Dennis was recorded as the father of four children, but this number had dropped to only two in June 1848; by July 1848, only one child was listed. Was child mortality one of the issues behind Dennis’ repeated admissions to the asylum? There is nothing in his records that points to this, beyond the diminishing number of children, but it is something over which to speculate.

Dennis McNamara was a distressed, restless, and depressed Irish Catholic immigrant living in York County. He worried about his wife and children, felt homesick for Ireland, and, as the refugees from the Great Irish Famine poured into Toronto in the summer of 1847, was unable to find a job. For a period of four years, he was a repeated patient at the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, but not one who seemed to merit long-term care, perhaps because the province was paying for his confinement. One of the most striking (and ironic) features of Dennis’ file is not that he was discharged, but that the medical authorities insisted that he had been “cured” – again, and again, and again.