It was supposed to be just another day at the library. A great day, to be sure, but not one that would have life-changing effects.

But then I found out about Mary Boyd, and everything I had been working on paled by comparison. Time ceased to tick and began to flow. I was flooded by so many ideas and connections and possibilities that I couldn’t read or type fast enough.

A bit of context: last year, I had the immense good fortune to win a Fellowship in Canadian Studies at the British Library from the Canada-UK Foundation and the Eccles Centre. My plan to research the opinions of certain 19th century doctors in the UK, Ireland, and colonial Canada about cholera, typhus, migration, insanity, and the early days of modern obstetrics and gynaecology. I had called up a number of materials concerning Dr Joseph Workman, the Irish-born physician who had trained at McGill during the 1832 cholera epidemic, and then was in charge of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto from 1853 to 1875. Workman wrote a lot, and his articles on ‘madness’ were widely read on both sides of the Atlantic. The microfiche I had loaded into the machine had an intriguing title: Inquest on Mary Boyd, held at the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, Toronto, 5th and 6th May, 1868: Evidence and Correspondence in Full. Wordy, but interesting.

Then I started reading.

Then I couldn’t stop reading.

Then I started swearing under my breath.

Then I just cursed flat out and just as quickly hid behind the large viewing screen, hoping no one was looking, since a loud “F*cking hell!” in the British Library just isn’t done.

The other bit of context: less than a week earlier, the American Supreme Court had overturned Roe v. Wade. Abortions were a leading topic of discussion for governments in the USA, the UK, and back home in Canada. What happened to Mary Boyd in Toronto 1868 suddenly felt uncomfortably current.

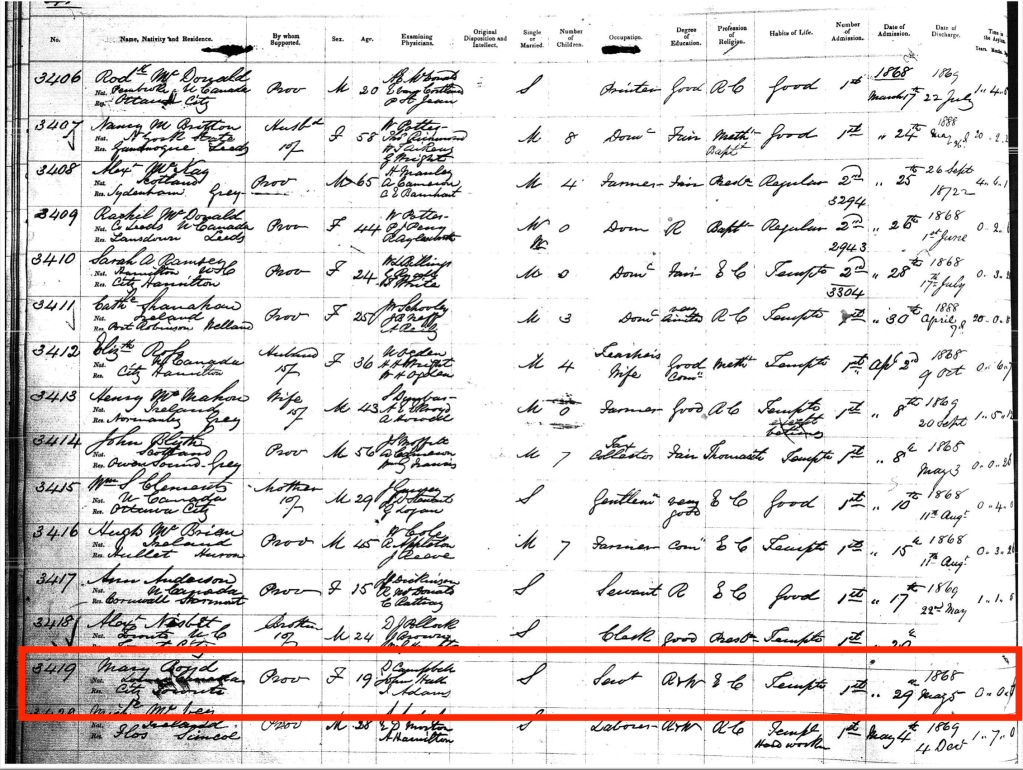

Joseph Workman had been the presiding physician when Mary Boyd, a nineteen-year-old Irish Quebecker, had arrived at the asylum in a dreadful state: she had tried to kill herself twice in a single week, and nearly succeeded the second time. Still alive, but in great pain and trauma from a knife wound to her throat, she had been taken to the asylum at night by her employer, Dr Duncan Campbell, and Campbell’s teenaged son, Lorne. She died six days later.

But what happened at the official coroner’s inquest into her death, and in the Toronto newspapers for the following month, gave Mary’s story a national spotlight. You can hear a full, detailed version of it here.

To make a long story short, it seems quite clear that Dr Campbell electrocuted Mary in the hope of causing an abortion after she revealed that his son had had sex with her. Mary Boyd’s story involves all sorts of topics and themes: virginity, sexual consent, sexual assault, medical experimentation, suicide, abuse of power, the control of women’s bodies, professional rivalries, and class – just to name a few.

Mary died over 155 years ago. Her story, with all of its various twists and turns, is now the main focus of my research as the GMM Project – focusing on the treatment of the Irish in Canadian lunatic asylums – and the MTC Project – focusing on the experiences of migrating pregnant women and mothers in the colonial medical system – begin to intertwine.

On the one hand, I feel tremendously excited to have found this story and to be able to write about it over the next year; on the other hand, these things really happened to Mary. She’s not a character in a novel. She was real, and she died horribly.

One always has to be objective about the past, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t feel anything, either. As I start writing the manuscript about the body of Mary Boyd, I know I’ll be feeling a lot, and then going on many walks to deal with it.

~JMcG